Diagnosis and management of common eyelid conditions

As eyelids are very visible to everyone, lesions occurring on the lids are usually detected early.

Similarly, conditions such as as excessive watering from the eye (epiphora) can be quite troublesome, especially in winter and the flu season, and many people will seek help earlier rather than later because of the degree of annoyance it causes.

One of the more common benign eyelid conditions encountered in general practice is a chalazion. This is a granulomatous inflammation of the Meibomian glands in the lids, and presents as a firm swelling in the upper or lower lid, usually non-tender, rounded, and well delineated. It is easily treated with warm compresses and antibiotic ointment.

Rarely it will affect vision, with patients most frequently describing it as annoying rather than anything else. Should it persist, referral to an ophthalmologist for incision and curettage should be considered.

Closely related to the chalazion (Figure 1) is a slightly more serious inflammatory condition: a stye. A stye is a painful, pus-filled cystic lesion occurring on the eyelid. There is a risk that a stye could proceed to preseptal cellulitis, which can lead to severe complications. In addition to the standard antibiotic eye drops and ointment, oral antibiotics may be warranted in this case.

Another very important condition of the eyelid that should not be missed is preseptal and orbital cellulitis. (Figure 2) These conditions are considered ocular emergencies as there is a high risk of the infection and inflammation spreading to the orbital tissues and the brain.

The condition can be recognised by diffuse swelling of the eyelids, with associated pain on touching the eye and painful or reduced eye muscle movements. Once the conjunctiva and eye movements are affected, or involvement of the pupil occurs, suspicion should be high for orbital cellulitis.

Orbital cellulitis may or may not be preceded by dacryoadenitis, which is inflammation of the lacrimal gland. Dacryoadenitis is often very painful, with a very tender lump palpable in the lateral upper lid. Most patients will object to letting you touch it.

Immediate referral to an ophthalmologist is necessary for hospital admission and intravenous antibiotics.

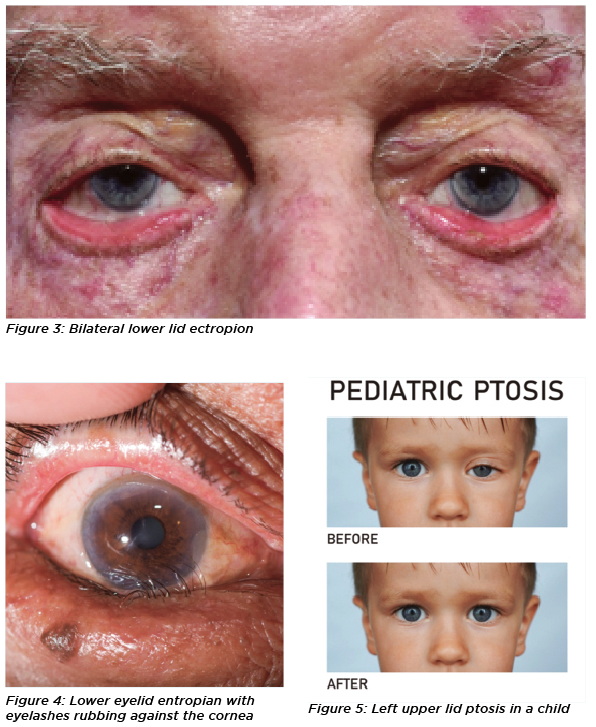

Another less dangerous, but common condition is an ectropion, seen as an out-turning of the lower lid. (Figure 3)

An ectropion may involve the tear duct opening (punctum) so that it positioned away from the globe, rendering it ineffective as a drain for the tears. Patients often complain of a constant flow of tears down their faces without reason.

Conservative management involves the use of lubricating eye drops and ointment, while definitive management requires surgery to correct the lid position.

More worrisome is the condition known as entropion, which is an in-turning of the eyelid margin. (Figure 4)

The danger with entropion, is that the eyelashes are in contact with the cornea and conjunctiva, causing irritation and possible corneal scarring with eventual loss of vision.

Initial treatment is with lubricating drops and ointment with a bandage contact lens to protect the cornea. However, some form of surgery is usually required fairly quickly.

Blepharitis is also a very common eyelid condition. According to a recent survey of American ophthalmologists and optometrists, between 37% and 47% of their patients have had blepharitis at some point, with younger patients reporting the condition more commonly.

However in our clinical setting, blepharitis tends to be a condition more frequently affecting the elderly.

Blepharitis is characterised by soreness of the eyelid margins and dry eye symptoms. It is caused by the blockage of the Meibomian glands (which provide lubricant to the ocularsurface) by an overgrowth of the bacteria that live on the eyelid margins. It appears as little swollen globules at the eyelid margin, just behind the lashes.

Treatment of blepharitis includes lid scrubs with cotton tips, warm compresses as often as possible and warm massage to the eyelid to loosen the oils and relieve the blocked glands. Antibiotic ointment and lubricating drops can be given to relieve the symptoms.

A similar condition is ocular rosacea. Ocular rosacea is an inflammatory condition involving the skin of the face and chest. Patients often have a “ruddy” complexion,redness and painful irritation of the eyes, as well as a sensitivity to light (photophobia). In severe cases, the cornea may be affected as well, leading to ulceration. The cause of ocular rosacea is unknown, but treatment is the same as for blepharitis.

Epiphora or constant watery eyes, is also a very common complaint and can be due to a number of causes, such as afore mentioned ectropion, a blockage anywhere along the tear duct system, or dry eye syndrome.

Initial management should include investigation of a cause, and if possible treating that cause. However, if no modifiable cause is found conservative management is with lubricating drops and ointment.

Blepharoptosis, or ptosis, is a common eyelid condition. (Figure 5) It is defined as drooping of the eyelid margin occurs below the 2mm normal from the superior part of the cornea. It can be congenital, and can occur in both children and adults.

It has a multitude of causes ranging from maldevelpment of the levator muscle in congenital ptosis to myasthenia gravis or the age-related changes in the levator muscle in adults. Some parents have reported: “My child looks sleepy, and he walks around with his neck tilted upwards.”

Other causes could be neurological, such as Marcus-Gunn jaw winking (eyelid level moves up and down with chewing or movement of the jaw), or a third nerve palsy, (dilated pupil, eye looking down and out). Third nerve palsy is a serious finding as it may indicate an intracranial aneurysm or tumour. Immediate specialist referral is recommended

Ptosis may also be caused by trauma.

The consequences of a persistent, untreated ptosis in children, may include poor development of their vision and neck pain, as well as a poor cosmetic outlook. In adults, a ptosis might affect their vision due to obstruction. Management is usually surgical, to correct lid height, after excluding sinister or reversible causes.

There are also a couple of tumours which affect the eyelids. Benign naevi, which can be pigmented or non-pigmented are relatively harmless. Another benign condition is papillomasare stalk-like growths akin to a mulberry, which and arise from the eyelid skin or margin. These are commonly referred to as warts or skin tags.

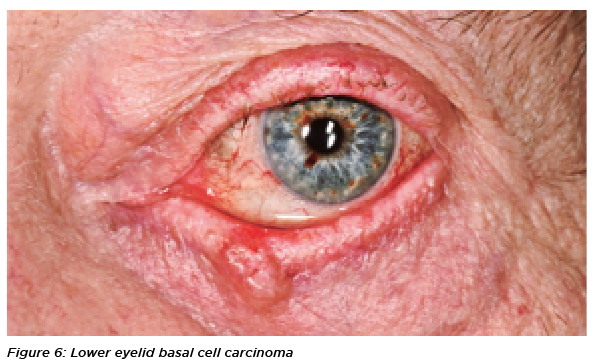

High levels of sun exposure has meant most Australians are prone to developing skin cancer, including melanomas, basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Research from the Cancer Council of Australia shows that as many as two out of three Australians will develop a skin cancer by age 70 with the numbers diagnosed increasing from 3,526 in 1982 to 13,280 in 2016.

One of the more common skin cancers is basal cell carcinomas, which presents as a raised growth on the eyelid margin or around the eyelid, with pearly/shiny borders, sometimes with a depression/crater in its centre, blood vessels on its surface, and loss of lashes. (Figure 6)

It may disfigure the lid margin structure depending on the severity and may also bleed. Its management involves initial biopsy for confirmation and then consequent excision of the tumour with lid repair.

Less common, but more dangerous is squamous cell carcinoma, which tends to metastasise much earlier than BCCs. It may evolve from a cutaneous horn, actinic keratosis or SCC-in situ.

It grows fairly quickly and has everted edges and ulceration and no shiny borders. Confirmation by biopsy is the gold standard of diagnosis, then excision with reconstruction of the eyelid.

Risk factors for these skin cancers are excessive exposure to ultraviolet radiation (sunlight), family history and genetic susceptibility.

Encouraging sun protection is another important aspect of management to prevent further recurrence of these cancers.

Images used under licence from Shutterstock.com and sciencephotolibrary.com

Associate Professor Raf Ghabrial graduated from the University of Sydney, with Honours in Medicine in 1988. He since trained as an ophthalmologist at the Sydney Eye Hospital. Afterwards, he gained unique experience in oculoplastic surgery in the United Kingdom and in the United States where he was appointed to New York University, the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary and the Manhattan Eye Ear and Throat Hospital.

Dr Amaka Vera Ofoegbu is a oculoplastic surgery fellow as Sydney Eye Hospital. She trained in ophthamology at Lagos State University Teaching Hospital in Nigeria and completed an oculoplastic surgery fellowship at University of Auckland, NZ

References

- Friedman NJ, Kaiser PK; The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. 3rd Ed. Massachusetts. Elsevier Inc. 2012.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2016. Skin Cancer in Australia. [Internet]. Cat. No. CAN 96. Canberra: AIHW. [Cited 2019 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au.